Bible Study on Habakkuk

https://bibleproject.com/guides/book-of-habakkuk/

1. Historical & Political Framework

- Timeframe: Habakkuk prophesied in the late 7th century BCE (around 609–597 BCE).

- Political Climate:

- Assyria, the once-great empire, had collapsed (Nineveh fell in 612 BCE).

- Babylon (Chaldea) was rising in power under King Nebuchadnezzar.

- Judah was caught between fading Assyria, aggressive Egypt, and the ascendant Babylon.

- Josiah, Judah’s reformer king, had recently died (609 BCE). His death left Judah politically unstable.

- Corruption, injustice, and violence were rampant in society.

Habakkuk wrestles with the question: Why does God tolerate evil? Why do the wicked prosper while the righteous suffer?

2. Jewish Scholar’s Perspective

- Hebrew name: חֲבַקּוּק (Ḥavakuk) — means “embrace.” Rabbinic tradition says the prophet’s name reflects God embracing Israel in their suffering.

- Unique feature: Habakkuk questions God openly. Unlike other prophets who speak for God, he speaks to God with raw honesty.

- Rabbinic insight: The Talmud (Makkot 24a) notes that Habakkuk distilled the entire Torah into one principle:

“The righteous shall live by his faith” (Habakkuk 2:4).

- Jewish commentary (Rashi, Radak, Malbim):

- Rashi sees Habakkuk’s bold questioning as part of Israel’s relationship with God—faith is not blind but dialogical.

- Radak explains that God’s answer about the Chaldeans shows divine justice unfolds in history, not always immediately.

- Malbim emphasizes faith as patient trust that God governs the nations even when evil appears dominant.

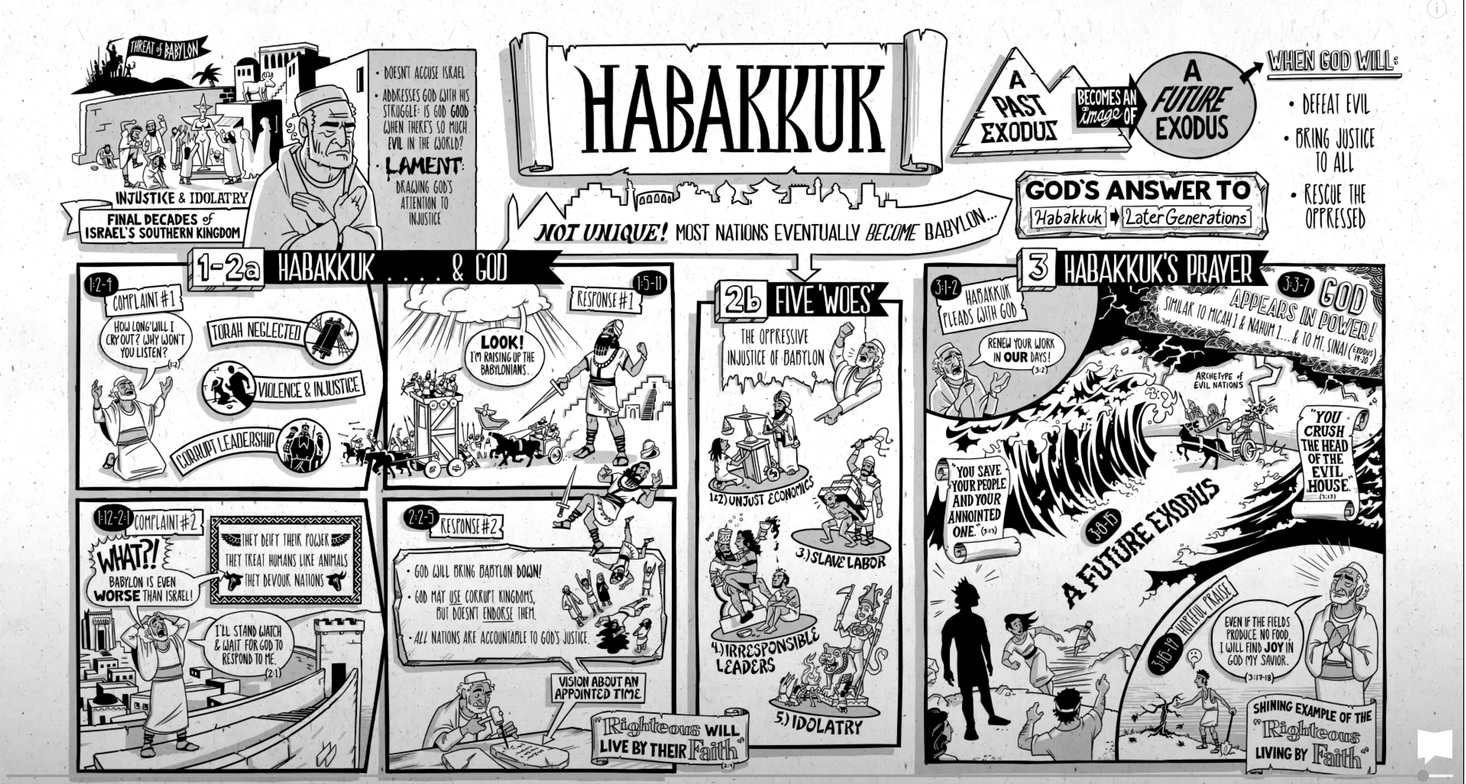

3. Chapter-by-Chapter Review

Chapter 1 – The Prophet’s Complaint

- Habakkuk questions why God allows injustice in Judah and why He will use Babylon (the Chaldeans), a violent nation, as His instrument.

- Theme: The problem of evil and divine justice.

- Jewish perspective: It is legitimate to cry out to God. Lament is part of covenant faith.

- Key Verse (Habakkuk 1:2, NKJV):

“O Lord, how long shall I cry, And You will not hear? Even cry out to You, ‘Violence!’ And You will not save.”

Chapter 2 – God’s Response & the Call to Faith

- God assures Habakkuk that judgment will come on the arrogant (the Babylonians) in His appointed time.

- The righteous are called to live faithfully and patiently until justice comes.

- Includes the famous “woe oracles” against oppressors (2:6–20).

- Jewish perspective: Faith (emunah) means loyalty, trust, and steadfastness, not just belief. It is active, lived obedience while waiting for God’s justice.

- Key Verse (Habakkuk 2:4, NKJV):

“Behold the proud, His soul is not upright in him; But the just shall live by his faith.”

Chapter 3 – The Prophet’s Prayer

- A poetic prayer/psalm describing God’s mighty acts in Israel’s history (Exodus, Sinai, conquest).

- Habakkuk ends in trust: even if crops fail and herds die, he will rejoice in God.

- Theme: From lament to faith-filled worship.

- Jewish perspective: This is recited in Jewish liturgy (Habakkuk 3:3–19 is read in synagogue on Shavuot), reminding Israel that God’s deliverance in the past assures His future salvation.

- Key Verse (Habakkuk 3:17–18, NKJV):

“Though the fig tree may not blossom, Nor fruit be on the vines;

Though the labor of the olive may fail, And the fields yield no food;

Though the flock may be cut off from the fold, And there be no herd in the stalls—

Yet I will rejoice in the Lord, I will joy in the God of my salvation.”

4. Summary Themes

- Wrestling with God is part of faith — Habakkuk teaches that questioning God does not equal lack of belief; it can be an act of deep trust.

- Divine justice is certain but not immediate — God’s timing may not match human expectation, but evil will not triumph forever.

- Faith = active trust — “The just shall live by his faith” is central not only in Judaism but also later in Christian writings.

- Worship is the ultimate response — Despite circumstances, the prophet ends in joy and trust.

In short: From a Jewish scholar’s lens, Habakkuk models covenantal honesty: protest, dialogue, faith, and praise. He places Israel’s political suffering under the larger framework of God’s justice and sovereignty, teaching that true righteousness is found in faithful perseverance.